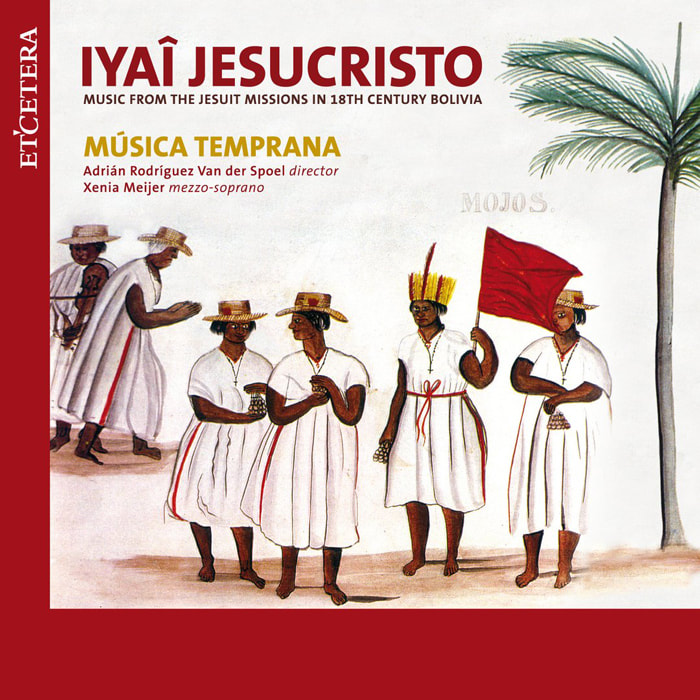

The musical heritage of the Jesuit mission posts situated in the vicinity of the rivers Amazonas, Paraná, and Uruguay is interesting, even fascinating. By now, two music archives have been compiled, consisting of hundreds of works going back to the 18th century, the hey-day of these mission posts. The repertoire shows strong Italian influences, but also distinctively exotic elements, both in the treatment of harmony and melody and in the instrumentation. Since the liturgical services in the mission posts were held in Latin as well as in the indigenous languages, the musical settings of many motets were based on Guarani and Chiquitan texts. After the missionaries had been condemned to exile, their posts, many of them very efficiently run, were used for various other purposes: some local people managed to maintain their social structures; others fought against the exile of the missionaries, to no effect; again others set up new posts in the jungle. The 1950s saw the beginning of the restoration of the churches in the Bolivian part of Chiquitos and Moxos in the Amazone lowlands. Not long thereafter, the first musical notations were discovered, having been saved as precious cultural items by the local population. The ensemble Música Temprana performs this repertoire together with Bolivian musicians originating from the area, and pays regular visits to the region in order to learn more about the way of life and other characteristics of these indigenous communities.